Women’s financial security: five levers of change

by Zoe Pappas, Dr James Mills & Richard Waid

Right Thinking

Over the past century Australia has been a world leader in legislating for gender equality. However true equality is about more than just equal rights, it’s also about changing attitudes. Unfortunately, societal norms change at a glacial pace, and though few today would still argue for differentiated gender roles, a strong gender asymmetry persists.

In this article we present a framework for assessing the disadvantages women face and outline five levers of change for addressing these issues. These ideas were developed in preparation for and during Right Lane’s inaugural 2018 Women’s Financial Security Forum.

On 13 September 2018, a group of passionate and like-minded people came together at the first Right Lane Women’s Financial Security Forum, with an aim to work on developing breakthrough ideas to help lift Australian women out of financial hardship.

Historically Australia has been a world leader on gender equality. In 1902, only a year after Federation, Australia became the second country in the world to give women the right to vote and to stand for parliament; it took over a quarter of a century for our erstwhile colonial parent to follow suit. Since this triumph, Australia has taken great strides towards creating an egalitarian society through legislation such as the Sex Discrimination Act of 1984 and the Workplace Gender Equality Act of 2012. However, despite this progress, a stark disparity remains between the financial challenges faced by Australian men and women.

Gender biases are pervasive in today’s society

For many people, ‘gender equality’ is synonymous with ‘equal rights’. However, while certainly a prerequisite, merely securing equal rights is not sufficient to deliver gender equality. If we look beyond the legislated rights, we find that the prejudices of history echo through to the everyday experiences of Australian women. In this article we focus upon one such persevering disadvantage: the systemic biases inherent in today’s society which compromise the financial security of Australian women. Our analysis highlights several pervasive impediments to women’s financial security that engender a heightened vulnerability to changes in their financial position. As a result, financial ‘shocks’ are more likely to push women towards a position of financial hardship.

The financial disadvantages faced by Australian women

There are two primary disadvantages that adversely impact the ability of Australian women to achieve and maintain, financial security. Firstly, despite a positive trend in recent years, women continue to be significantly underrepresented in full-time employment, forming only 37% of the Australian full-time workforce (The Melbourne Institute 2018). Secondly, women who are in full-time work, take 22% less in average total remuneration than men (WGEA 2018), reflecting a $500 gap in weekly earnings.

Though a range of factors may contribute to these two effects, perhaps the most significant impact arises from societal expectations relating to, and the observed reality of, the role women play in household and familial care. On average women spend 26 hours more per week on these duties than men, limiting the time they can commit to their professional careers.

By the time of retirement, the cumulative effect of these headwinds results in a $131k gap in the average superannuation balance between men and women, a staggering 42% shortfall (ASFA 2018). These disadvantages mean many Australian women struggle to achieve financial security and are therefore less able to absorb financial shocks.

A crisis waiting to happen

For the large number of Australian women who endure this state of heightened financial vulnerability, one or more financial shocks can be enough to push them into financial hardship. Financial shocks may have many causes including sudden job loss, the inability to work due to disability or illness and reductions in welfare payments. For women who are already delicately balancing their financing, any one of these shocks can be enough. In a recent survey three out of five women indicated they were unsure they had the resources to withstand a financial shock (CBA 2017).

In addition to financial shocks, a variety of domestic influences can lead to financial hardship. For example, separation or divorce from a long-term partner, domestic abuse, or sudden bereavement are all capable of driving women in to financial hardship. In Australia, one in three marriages ends in divorce (AMP and NATSEM 2016), with women most often becoming the primary care giver to their children while receiving significantly reduced support from their former partners. For other women, violent domestic situations can drive them, and their children, from the family home. The prevalence of domestic violence in Australia often goes unobserved. However, a recent survey found that one in three women have experienced some form of physical violence from the age of 15 (ANROWS 2018). For those women affected by domestic violence, escaping can thrust them into financial hardship as they must contend with finding and funding safe domestic arrangements. Coping with separation, abuse and sudden bereavement are significant challenges for anyone who must face them. However, women whose financial resilience is already compromised by the pervasive disadvantages they face are at a much higher risk of falling into financial hardship.

Working towards a solution

In September 2018 we hosted a Women’s Financial Security Forum with over 40 like-minded and passionate leaders to generate ideas for addressing the systemic disadvantages that women face. In preparation for this session we created a framework to structure the way that we observe and respond to this issue.

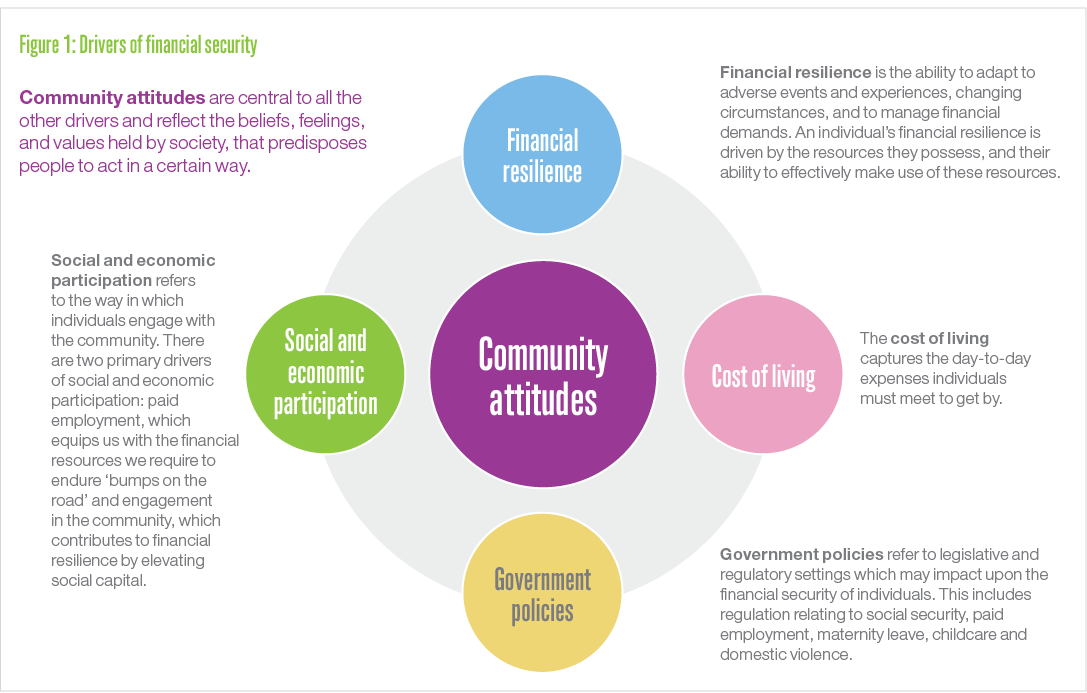

Our framework identifies five drivers of financial security for women in Australia, and the systemic issues relating to each driver, which put women at increased risk of financial hardship (See figure 1: Drivers of financial security).

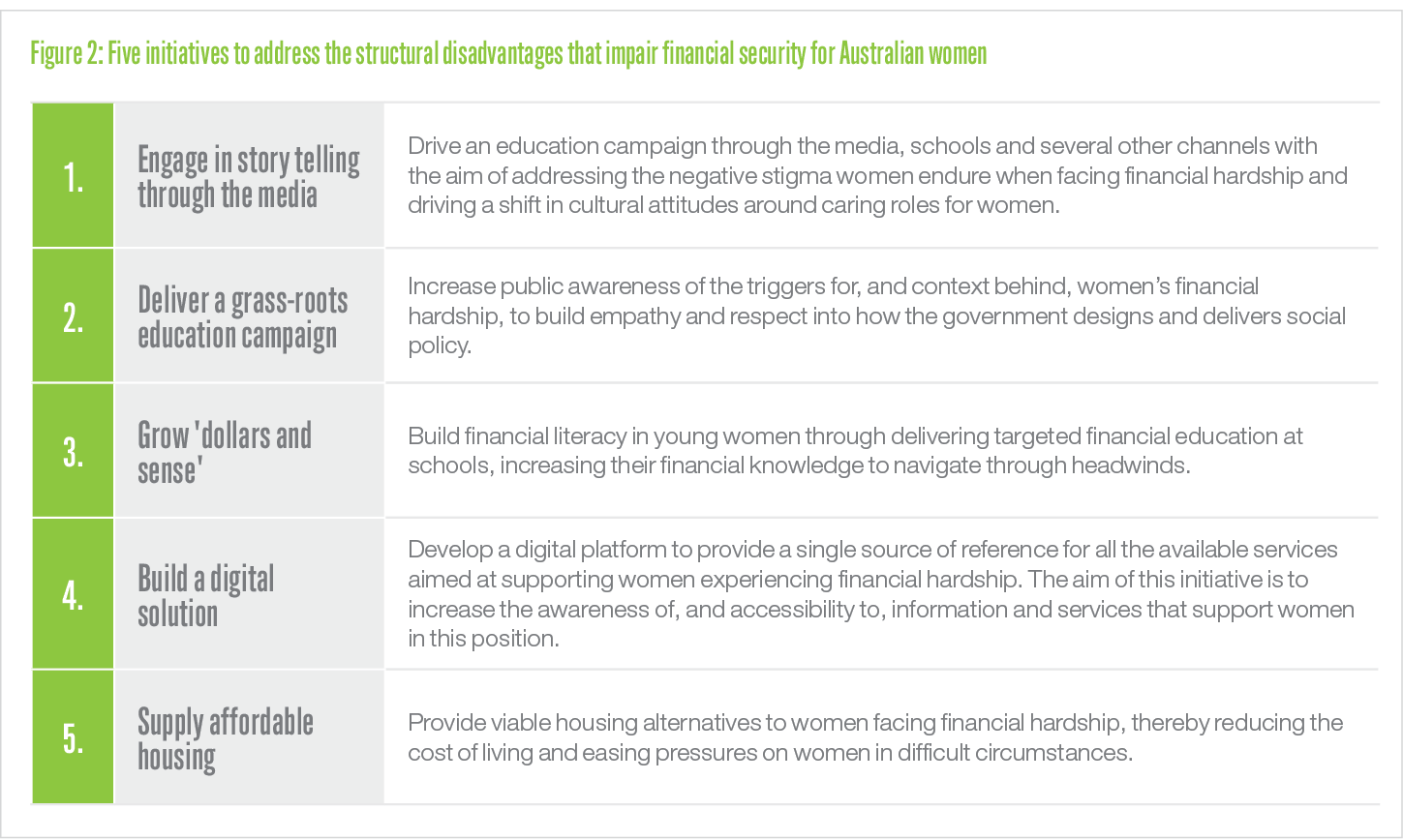

During the Women’s Financial Security Forum participants developed and prioritised five initiatives to help address the structural disadvantages that impair financial security for Australian women. (See figure 2: Five initiatives to address the structural disadvantages that impair financial security for Australian women).

References

AMP and NATSEM 2016, Divorce: For richer, or poorer, <https://natsem.canberra.edu.au/storage/1-December%2013%20-%20AMP.NATSEM39%20-%20For%20Richer%20For%20Poorer%20-%20Report%20-%20FINAL%20(2).pdf>.

ANROWS 2018, Violence against women: Key statistics, Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety, viewed 29 November 2018, <https://anrows.org.au/sites/default/files/Fast%20Facts%20-%20Violence%20against%20women%20key%20statistics.pdf>.

ASFA 2018, Superannuation account balances by age and gender, viewed 4 December 2018, <https://www.superannuation.asn.au/ArticleDocuments/359/1710_Superannuation_account_balances_by_age_and_gender.pdf.aspx?Embed=Y>.

CBA 2017, Enabling change: a fresh perspective on women’s financial security, Commonwealth Bank of Australia, viewed 7 December, <https://www.commbank.com.au/content/dam/caas/newsroom/docs/2017-06-28-financial-security-report.pdf>.

The Melbourne Institute 2018, The Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia Survey (HILDA): Selected Findings from Waves 1 to 16, viewed 7 December 2018, <https://melbourneinstitute.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/2839919/2018-HILDA-SR-for-web.pdf>.

WGEA 2018, Workplace Gender Equality Agency, viewed December 2018, <http://data.wgea.gov.au/industries/1#pay_equity_content>.

© 2018 Right Lane Consulting

We hope the ideas presented here have given you something new to think about. We would love the opportunity to discuss them with you in more detail. Get in touch today.