Better decision-making: A key to unlocking organisational effectiveness

by Linda Deng

Right Thinking

In a previous Right Lane article ‘Organisations that deliver: five elements of strategy execution that set apart winning organisations’(Chhikara & Williams 2018), we discussed the importance of effective decision-making. If senior leaders are the ‘brain’ of the organisation and the employees are the ‘arms and legs’, then decision-making is the neurons that receive, process and transmit information throughout the body.

While working closely with our clients on their strategy and planning, we have observed that effective decision-making is a key to unlocking effectiveness.

Three steps to improve decision-making in an organisation are:

- Determine the decision-making ‘problem you are solving for’

- Identify and address the levers for decision-making that require improvement

- Bring the changes to life through a rapid test and learn approach, creating a viral effect throughout the organisation

Decision-making typically becomes more complex as organisations grow, the amount of data multiplies and team interactions morph from silos into an intricate web.

Executives will know if they need to review decision-making within their organisations if:

- The organisation has restructured or grown substantially in the recent past

- Decision-making is taking longer than expected

- Decisions that were already made are relitigated for no good reason

- Unintended or unfavourable consequences from decisions give rise to the question, ‘How did that decision get made?’

If one or more of these conditions are present, then there may be a problem with the what, how, who and when of decision-making.

From scores of relevant client engagements, we have observed that decision-making is a key to unlocking effective organisational effectiveness, including in the area of strategy execution where we do much of our work. For example, improving decision-making can enhance the speed and efficacy of initiative prioritisation and resource allocation.

This article outlines a framework and approach to improving decision-making in organisations.

1. Determine the problem or problems you are solving for

Organisations are collections of individuals and teams, with project-based or more permanent characteristics, and vertical, horizontal and diagonal dimensions. Within these complex systems, it can be difficult to determine the root cause of ineffective decision-making. But if it appears as though there is a problem – for example, there is recurrent feedback from employees or challenges experienced in the wake of poor decisions – then the first step is to do the ‘heavy lifting’ of problem diagnosis.

Problems may include a lack of rigour, unclear roles, differing expectations on the level of information required to make decisions or a lack of clarity relating to the organisation’s risk appetite.

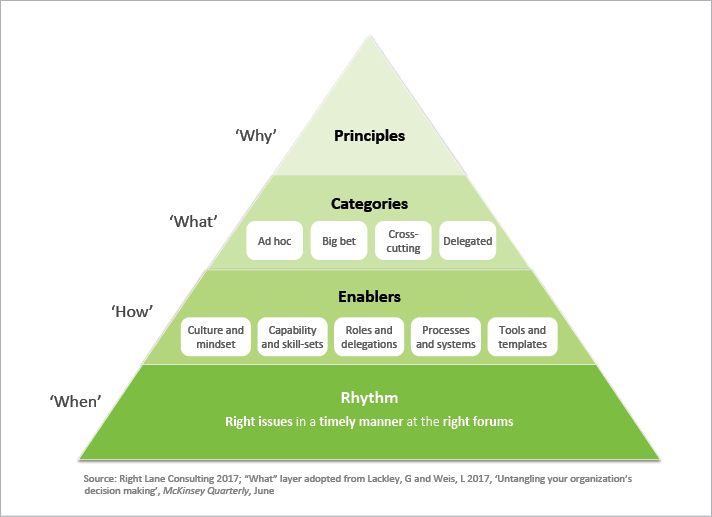

By engaging with a wide cohort of employees, it is possible to drill down and determine the causes of poor or ineffective decision-making. This will enable the leadership team to develop a ‘house view’ on the problem to be solved and identify the levers – principles of decision-making, categories of decisions, tools and enablers, the rhythm of decision-making – and how hard they need to be pulled to fix the problem. These levers are shown in Exhibit 1: Decision-making levers.

Exhibit 1: Decision-making levers

2. Identify and address the levers for decision-making that require improvement

Define the principles

Just as values set expectations for how employees should conduct themselves within organisations, decision-making principles signal the expectations of leadership with respect to decision-making.

Examples of decision-making principles are:

- Trust the decision-maker’s intent and capability

- Employ fact-based decision-making, but on the ‘balance of probabilities’,

not ‘beyond reasonable doubt’ - Build implementation into decision-making by clearly outlining what will be done, who by and when.

Categorise the decisions

Categorise the decisions

Organisations can make hundreds of decisions every day. These decisions range from automatic responses to familiar situations to those that require extensive analysis and debate in highly uncertain and unfamiliar domains.

The application of the decision-making principles will vary based on the decision category. Lackey and Weis’s ABCD model (2017) is one approach to categorising decisions based on their frequency and familiarity. It divides decisions into four types:

- Big bet decisions have major consequences for the organisation and often involve unfamiliar situations with unclear right or wrong choices

- Cross-cutting decisions are made frequently and require broad collaboration across organisational boundaries

- Delegated decisions are made frequently and can be assigned to an individual or to a working team, with limited input from others

- Ad hoc decisions arise infrequently and have a low impact on the broader organisation.

Leaders of some organisations we’ve worked with and observed – including those who believe that some of their decision-making processes are underdone or overblown – have found it helpful to categorise their major decisions and agree an appropriate approach for each category.

Provide tools

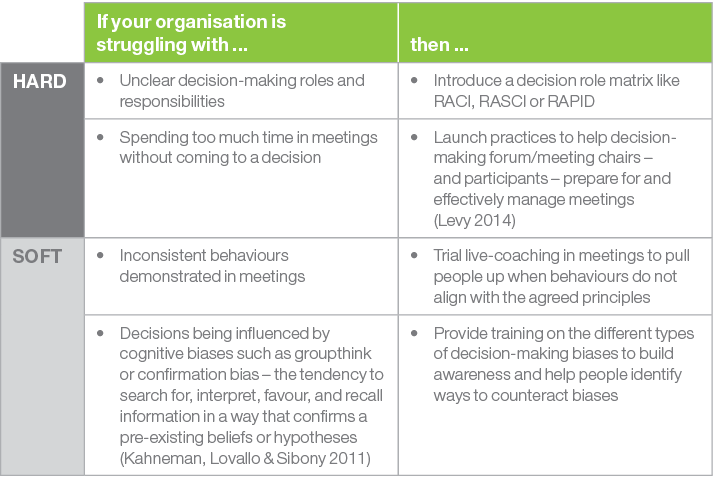

To enable the principles and categorisation framework, organisations need to put in

place the appropriate ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ tools that enable employees to make decisions.

The ‘hard’ tools involve clarifying roles and delegations; developing decision-making processes and systems; and providing tools and templates to assist in decision-making.

The ‘soft’ tools include the ways of working within and between teams; the culture and mindsets of the employees; capabilities and skills; and ensuring that principles are matched with behaviours.

The following table shows different tools that might be applied depending on the context.

In addition, we’ve often found it helpful to refresh current governance arrangements that may constrain employees’ decision-making, such as delegations of authority and committee charters, to reflect the new approach.

Improve the rhythm

Depending on the context, the timeliness, sequence and frequency of decision-making can be just as important as the principles, categorisation and tools. What decision-making forums have been established in the organisation? How does each forum interact with interdependent forums? Are there too many forums? A scan across the organisation will provide a baseline of information about the rhythm of decision-making.

Once you have a baseline, key questions in reviewing the rhythm of decision-making include:

- Do these decisions need to be made in a forum?

- Is the current decision-making forum the right one?

- Is the forum held with the appropriate frequency to drive the operational activity?

- Does the forum occur at an appropriate time of the week/month/year given the inputs required and the outputs expected from the forum?

The rhythm of decision-making will drive the operating rhythm of the organisation.

3. Bring the changes to life through a rapid test and learn approach

Regardless of which decision-making levers need to be pulled, the change needs to be embedded in the organisation. Changing ways of working, as with any cultural change, is comprised of many small steps to build momentum, demonstrate the principles in action and create a viral effect within the organisation.

The improvements to decision-making can only be ingrained in the organisation by applying the levers on a day to day basis. Start by piloting the decision-making levers on simple decisions then try to tackle more complex ones. The entire process may take three to six months to design and implement, but the potential to make faster and better decisions should make it a worthwhile exercise.

References

Kahneman, D, Lovallo, D & Sibony, O 2011, ‘The big idea: Before you make that big decision’, Harvard Business Review, June.

Lackley, G & Weis, L 2017, ‘Untangling your organisation’s decision making’, McKinsey Quarterly, June (‘Categories’ layer adopted from this framework).

Levy, M 2014, ‘We spend way too much time in meetings’, Right Lane Review, December.

For more information contact Linda Deng on linda.deng@rightlane.com.au

© 2018 Right Lane Consulting