The state of ethics in organisations: why can’t we (still) kick straight?

By Marc Levy

Right thinking: Have business ethics lost prominence in recent decades? Are business ethics like goal-kicking in Australian football, the only aspect that hasn’t improved in recent decades? Drawing on interviews with senior executives, this article examines the state of ethics in contemporary organisations and identifies 6 good practices to promote an ethical climate.

What happened to business ethics? When I was coming up in consulting in the 1990s, ethics was a popular topic: ethics training was commonplace in organisations; ethics experts were prominent in the management discourse; and there was a subject on it in my MBA course.

Ethics has remained an important part of our thinking at Right Lane (see Exhibit 1); however, I would argue that there is generally much less talk of business ethics today than in the ‘90s.

If I’m correct, and ethics has lost prominence, why is that? Surely, it is no less essential now than it was then. We’ve recently witnessed high profile ethical failings in professional services firms, financial institutions and mining companies, with disastrous consequences for vulnerable consumers, public trust and economic value.

Is ethical conduct like goal-kicking in Australian football, the one aspect of the discipline that hasn’t improved in recent decades?

I decided to ask some of our senior clients about the state of ethics in organisations, speaking with 5 CEOs and one Deputy CEO. Two interviewees were from for-profits (a healthcare company and a law firm); 2 from non-profits, both institutional investors; and 2 from government agencies.

I asked them about what ethics means to them and why ethics are important, about elevating ethics and handling ethical violations, about the payoff from ethical conduct and well-known cases of problematic conduct. I asked them whether they thought I was right, that ethics had receded in the managerial consciousness, and if so whether they thought that was because ethics had been displaced by other theories and practices of a virtuous kind, like purpose and values, ESG, stakeholder capitalism and shared value.

Exhibit 1 |

| I’ve been referring to Right Lane as an ethical consulting firm for many years. What I meant by that originally was that we chose to work with clients low on resources; we had inclusive ownership and a form of stakeholder governance; we chose not to serve clients in certain industries; we made our numbers transparent to our people; and we employed social procurement where possible. In recent years, we’ve attempted to be (even) more ‘mission authentic’ and resolve possible conflicts in our ownership structure by becoming primarily foundation-owned. More detail about our journey to become an ethical firm is included in this article I wrote last year, From profit and purpose to profit for purpose: Towards a more progressive professional services firm ownership model. Right-Lane-Review-Aug-2023-Right-Lane-Foundation.pdf (rightlane.com.au) |

Definitions and importance

I started the interviews looking to define terms – What is ethical business conduct and what is an ethical organisation? – and to get a sense of how much ethics matter today.

One interviewee said ethical business conduct is ‘doing the right thing, cognisant of the organisation’s place in society and its social license, and acting in accordance with an agreed set of values.’

Another said, ‘It goes to values, but for me it’s more about behaviours. You can have a virtuous mission and values, with ordinary behaviours … a lot of it is how you go about things, how you treat people when faced with ethical dilemmas .. . that goes to the heart of being an ethical organisation.’

In discussing the importance of ethics, some interviewees pointed to the relationship between ethics and trust:

‘Ethics is the basis of trust …’

‘… trust is the most important thing and there is no trust without ethics.’

‘Trust comes from people of ethical or good character … good judgement.’

This link to trust seems particularly germane in sectors that benefit from public support, like healthcare and superannuation: ‘In an industry like ours, I have to believe that organisations are acting ethically … we have to behave ethically and keep patients uppermost in our minds … to have a trusted place in society’. And one of the super fund CEOs: ‘We are entrusted with tens of billions of dollars of other people’s money in a compulsory system … this potentially creates a platform to do good and bad things … rightly, as a consequence, people want to know what we do and how.’

Elevating ethics

I asked interviewees how we could elevate ethics beyond a ‘violation framing’ to create a ‘pro-ethical’ climate. Some interviewees thought elevating ethics was indeed possible and worth doing. A number mentioned decision making as a realm where ethics could be elevated:

‘… put the patient at the centre of everything … don’t do anything without reference to patients … make that part of the fabric of the organisation.’

‘It’s important that we walk the talk … decisions are made in a way that is ethical and the reasons why communicated.’

Others were more circumspect, even sceptical about elevating ethics:

‘It’s not something you can decide [to do]; it’s part of who you are, so you’ve got to have people around you … relationships with people of that ilk.’

‘It’s hard to train for ethics. John Cain never used the franking machine … [he] always bought his own stamps.’

Domains of an ethical organisation

I gave interviewees a list of domains of an ‘ethical organisation’ (see Exhibit 2). I asked which were the most important to them and what they were trying to do in these areas. The green shading shows those that were rated highest. Number 9 accountability and transparency received the most votes overall.

Exhibit 2

Source: Right Lane Consulting. (2024).

Interviewees said that an organisation’s purpose and ambition were means of communicating an ethical intent in a shorthand form that is appealing to staff. However, that isn’t enough. As one interviewee said:

‘I think … it’s a given … you need to go far beyond that … take it down to the next level for staff to, say, an employee charter or client promise’.

Governance and compliance are important ‘[as a public sector organisation] because of the scrutiny we come under’; ‘knowing there are guardrails gives a level of comfort to the top team and board’.

As noted above, decision making and making choices are how ethical conduct often manifests. One interviewee said that ethical conduct is observed when ‘the right people, have the right inputs and consider both can we do it and should we do it … and we wouldn’t be concerned if anyone, anywhere, knew about it.’

Regarding accountability and transparency, interviewees’ input centred on clarity of expectations:

‘You have to be clear about what you are doing and what you expect.’

‘You can manage ethical behaviour by being clearer about expectations … this is what we expect and what you can expect.’

Some interviewees said that two or more of these dimensions go hand in hand; for example, ‘I would use culture and inclusion and accountability and transparency in tandem’.

Ethical theories

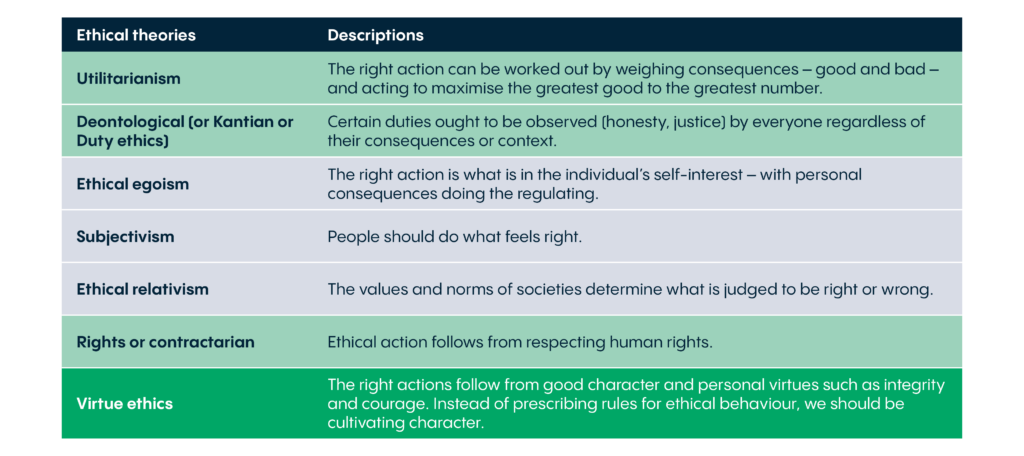

I shared with interviewees a list of theories from the above mentioned MBA course (Sinclair 1996) and asked them to tell me which ones resonated with them. These are shown in Exhibit 3. The green shading in the table shows the top 4 results, with ‘virtue ethics’ receiving the most votes overall.

Exhibit 3

Interviewees offered a range of illuminating reasons for these preferences; for example, ‘Human rights are always a fundamental, foundational piece’; and ‘I’m a pragmatist. Virtue ethics give you foundations you can weigh up’.

Referencing complexity, some interviewees were sceptical of utilitarianism and more definitive, absolutist theories like duty ethics:

‘The ends don’t always justify the means in a complex world.’

‘We don’t have the luxury of black and white; things are complex.’

Most interviewees pointed out the benefits of using these theoretical framings as different lenses: ‘The basis for ethic decision making is the interplay between them.’

Handling ethical violations

Where there is a clear breach of the law, a compliance code or the organisation’s policies, interviewees generally said the response should be swift, formal and consistent with performance management, grievance and dispute processes:

‘[In healthcare] there is a strong regulatory framework around compliance breaches, whistle-blower protections, a focus on patient safety.’

In other cases – in grey areas – managers should first seek to understand:

‘For the more day-to-day ethical breaches, I’d seek to know why. Why did you think that was the right thing to do? How did you get to that decision, using what process? It can sometimes come back to [the design of incentives], making sure people are not encouraged to put personal gain ahead of the needs of the patient community.’

Hardwiring ethics versus culture

Interviewees said both were important, hardwiring ethics and nurturing an ethical culture:

‘You need both. You can’t rely on policy all the time. You also need a culture of ethical conduct, and you have to have policies and structures [especially] for new people.’

‘A lot of it is in the Corporations Law … safeguards … but that won’t necessarily drive behaviour, so it becomes more about values, culture, transparency.’

Formal codes can go too far. ‘[Our] industry code has been revamped to [become] more values based. It went into great detail … people stopped thinking. Things can get out of balance with [too much] hardwiring and rules. People in Sicily are better drivers with no rules … Step back and talk about who we are trying to protect, so that people appreciate why.’

Governance structures and ownership

Participants noted that alternative governance arrangements give rise to different expectations relating to ethics:

‘The independence of the organisation and our governance is established under the Act … Being a public servant … there is more [guidance] than you would otherwise have.’

‘As a professional firm] I don’t know, it doesn’t inhibit us, but if I think of say an industry super fund, that definitely helps them [having as a legal reference point] “acting in members’ best interests”. Ours is probably better than a corporate model because we are interested in the outcomes over the long term …’

‘There is more transparency as a listed organisation … activist shareholders … an ESG framework … adherence to standards.’

Professional advisors

In the interviews, I referred to cases of problematic conduct from professional services firms and asked whether interviewees had any expectations of their professional advisors relating to ethical conduct:

‘Yes, it is reasonable to have expectations about how they conduct themselves, ethically, transparently, in good faith. You are allowing them access most others wouldn’t have … and you rely on [them having] basic ethical practices, like confidentiality, obviously.’

‘They have to comply with the laws … we ask them to sign agreements … Do we have expectations? Yes … about the way decisions are made … people assume because they are smart and professionals they’ll know what’s best … [got to] have checks and balances.’

‘There are a lot of transactional relationships in financial services, but the best ones have some kind of partnering and we can only really partner where we are values aligned … a common understanding and alignment probably improves the likelihood of success.’

A few interviewees were cynical about the ethics of advisors in the wake of recent scandals: ‘It’s hilarious that they preached to us about our governance and risk management frameworks.’

For some, professional advisor alignment was an area for more work. ‘We perhaps don’t do enough to think about the ethics of our partners. It’s very person-dependent; we haven’t matured our third party [protocols] to the extent I’d like. Do we feel ethically aligned? No. But we do say they should understand our perspective.’

Link to business outcomes

I asked interviewees about how being an ‘ethical organisation’ relates to other imperatives like financial results, customer satisfaction and staff engagement; and about whether they thought ethical behaviour led to favourable outcomes (and failures led to unfavourable ones):

‘Ethical behaviour – or the lack of it certainly shows up in outcomes: safety … fewer deaths and injuries … sustainability in what we do … society sees these things; they come to the surface.’

‘We want to be a trusted brand and ethics is imperative in that … [it impacts] how we attract our workforce, how we make decisions to put the organisation and our members in a better place.’

Ethics are important in the context of an organisation’s customer and employee value proposition:

‘If you are a values-led, ethical organisation, there will be a greater opportunity to connect to customers; it can be a real differentiator.’

‘I think when competing for talent, it has to be clear what you stand for, not just what you do.’

‘More and more people will join organisations they perceive to be ethical.’

In some cases, the question about how ethics sits with other imperatives led to discussions about balancing profitability and maintaining an organisation’s social license. ‘Everyone has to be able to hold these interests [in tension] and find a path that delivers for all.’

One CEO said that leaders’ thinking should be integrated and holistic. He used the example of the sustainable development goals: ‘… you can target a single SDG and screw up something else’.

Some interviewers did not want to ‘weigh up’ these concepts; for them, it isn’t a trade-off or a dichotomy, but something more fundamental:

‘You don’t do it for a payoff.’

Good practices

Reflecting on the interviews and the state of ethics in Australian organisations, I’ve identified 6 good practices to promote ethical conduct.

1. Call out business ethics and differentiate ethics from analogous concepts

Interviewees were engaged with my theory that business ethics have been displaced to some degree by other concepts, and some agreed with me:

‘Values are a more modern way of thinking about ethics.’

‘I don’t know the last time I heard someone talk about ethics in a business context. We use values, ESG and a range of other things, but we are talking about the same thing.’

Are we though?

I believe that the displacement of ethics has been detrimental. The other theories and practices I mentioned earlier (purpose, values, etc.) have their place; but I think it’s a different place. Promoting business ethics in organisations – including engaging with the language and the different theories, and having conversations about real world ethical dilemmas, the deep reservoir of cases we now have – can be richer, experientially, and more instructive, practically.

2. Set clear expectations

I am a fan of accountability expert Peter Bregman. He writes about ‘clear expectations’ being essential to ‘the right way to hold people accountable’, along with making sure they have the right capability, clear measurement, thoughtful feedback and appropriate consequences (Bregman 2016).

Some interviewees referred to the importance of clear expectations in relation to ethical conduct. Expectations can be set via formal procedures and standards:

‘We have a professional standards committee. Knowing that’s there helps.’

‘[We have] … an employee service charter and a complaints procedure.’

Expectations can also be clarified through intentional conversations. As Bregman says, ‘The first step is to be crystal clear about what you expect … It doesn’t all have to come from you. In fact, the more skilled your people are, the more ideas and strategies should be coming from them. Have a genuinely two-way conversation, and before it’s over, ask the other person to summarise the important pieces … to make sure you’re ending up on the same page.’ This is well illustrated by this quote from one of the interviews:

‘[Organisations have] moved from can we get away with it, to should we do it … and towards greater transparency … without transparency there’s no accountability.’

3. Model ethical conduct and send clear messages from the top

Interviewees spoke about what their organisations were doing to model ethical conduct:

‘Role modelling is important, as is telling stories, repetition.’

One CEO had developed an acronym to help his colleagues contemplate ethics. He wanted his organisation to be an ethical PLACE. People should act in accordance with the organisation’s Purpose and the Law; keep in mind All customers; alert to the Community’s and the board’s Expectations.

4. Train people in ethical decision making

Some organisations are using scenario-based training, particularly focusing on making decisions and choices ethically and handling ethical dilemmas.

I remember the transformative power of working through real-world cases in my MBA ethics class, expertly guided by Professor Amanda Sinclair. Observing ethics training in the years that followed, I saw the same ah-ha realisations in the expressions of numerous clients and colleagues.

5. Act emphatically on failings

The twin notions of ethical absolutism and relativism have been helpful to me as I’ve contemplated business ethics. Some situations are black and white; others are a shade of grey. Either way, in dealing with clear breaches or violations of laws or important policies or standards, or in addressing conduct where right and wrong is more subjective and difficult to discern, interviewees said taking deliberate and prompt action was the best course:

‘You’ve got to step in quickly. Doing so later is always harder.’

‘[In the less clear-cut cases] things like [personality] clashes and bullying … where there are failings, there is a lot of coaching, debriefings, a plan to work through it.’

6. Promote psychological safety and diversity

A number of the interviewees spoke about creating a safe environment for colleagues to raise concerns and challenge prevailing thinking:

‘Having worked in organisations with ethical failings, if there’s a culture of fear, if people don’t feel safe … they’ll walk past things … if you want an ethical [climate], people need to feel able to challenge …’

‘We hold focus groups and discussions … These led to “See something, say something, do something” … that’s shorthand for psychological safety … there are new questions in our colleague survey whereby people can speak without consequence … including do I feel that I can be heard …’

One interviewee highlighted the link between diversity and inclusion and ethical conduct:

‘Sympathy, good judgment, diversity including neurodiversity … these things make for ethical workplaces … kinder, safer workplaces and better decisions.’

So, why are we still experiencing the Juukan Gorges, the fees for no service scandals and professional confidentiality breaches? Why aren’t we (still) kicking straight?

Commentators in Australian football have said that goal kicking hasn’t improved because today’s game is so much faster; players fatigue, impacting execution of their skills. That sounds familiar to us when we contemplate business ethics. Every second business blurb seems to start with a version of ‘the unrelenting demands of unprecedented change’. However, just like blaming the demands of football for the missed goals, blaming the accelerating pace of change feels unsatisfying. As highlighted above, there are certainly things that leaders can do to foster an ethical climate within their organisations.

To improve conversion, goal kickers are told to slow down, develop and implement a stepwise routine that avoids common pitfalls, concentrate on process rather than outcome, and practice routinely. Based on the insights from the interviews, and good practices outlined above, that prescription is pertinent for leaders wanting to rehabilitate business ethics and build ethical organisations.

Want to know more? If you wo uld like to discuss this article in more detail, please contact

uld like to discuss this article in more detail, please contact

Dr Marc Levy: marc@rightlane.com.au

References

Bregman, P. (2016, January 11). The Right way to hold people accountable, Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2016/01/the-right-way-to-hold-people-accountable

Sinclair, A. (1996). Management, Ethics and Politics. [Class notes]. Melbourne Business School.